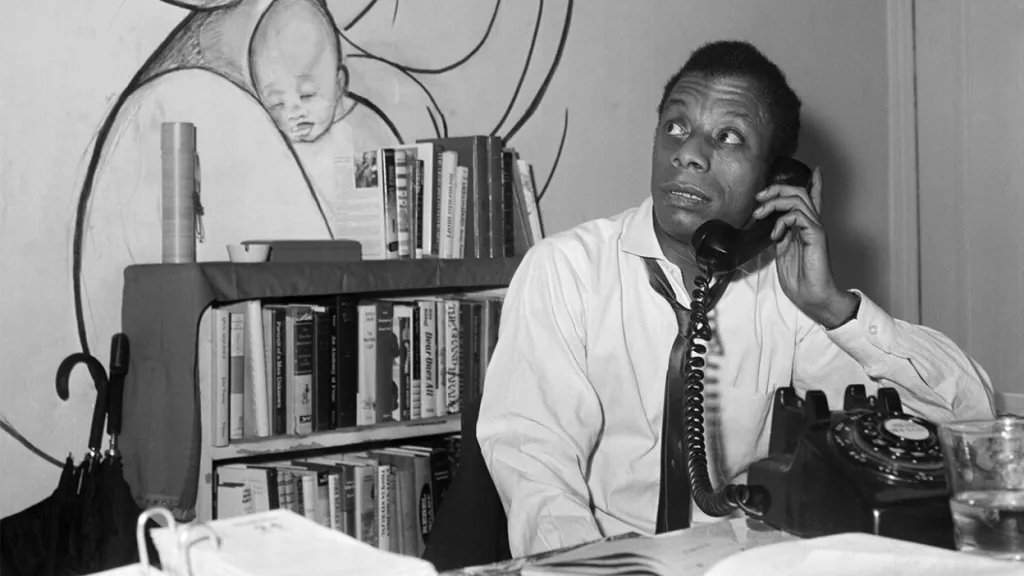

The Trouble Is In Us

James Baldwin in his apartment, New York, 1963|© Bettmann/Getty Images

This is the first of a series of twelve sketch texts. Each darns with words some things I see, do and experience in a given month, things which might be broadly understood as culture.

The idea occurred when reading On James Baldwin, by Colm Toibín, a book I ran through the gap between Christmas and New Year. In the chapter, The Private Life, Tóibín outlines at length the particular way in which Baldwin wrote from the private position. Baldwin was concerned with his particular place in the world, not for his own sake, but for ours. Each of us has a role in this history and we need to confront it, and for Baldwin, confrontation began at home.

The trouble is deeper than we wish to think: the trouble is in us, he also wrote in 1962 about urban loneliness, as part of an article about something else entirely. Here, while I write about things I have seen and done, I too am writing about something else. What that something is, is as yet unknown. But I believe by now, that in order to write at all, one has to simply accept the signs or directions are not clear at the outset. There is no other choice then but to write, to travel some route, to discover, and perhaps even to see.

Directions | Square de L’Ile du Pont, Paris | January 25th, 2025 | Emmett Scanlon

*****

The Future Is Real

Logan Roy (Brian Cox), at his desk in Scotland, Season 2, Episode 8 | Copyright HBO

January, I rewatch Succession.

I first watched it as we ate peas and porter on a couch nearly two years ago in Venice, on the short dark evenings post the long hot days of exhibition installation.

There is an episode when the tyrannical, violent father, Logan Roy goes to his birthplace of Dundee, Scotland to reluctantly receive an award. Once ‘home’ again, he is consistently, awkwardly, confronted with his past. He seems rattled, on shaky ground, uncharacteristically uncertain.

At one point Shiv, his daughter, the one most attuned to his moods, quips, Don’t like the past too much, huh?, to which Logan replies, I do. I do. It’s, uh… It’s just there’s so much of it. The future is real, but… the past, well it’s…all made up.

I spend a long time thinking about this.

*****

Our Parents Stories Are the Backdrop

Writer and sea farer Alexander McMaster reads aloud on the radio one Sunday morning. I have not heard his voice before. He sounds kind, I think, together in tone and thought. His is a soft, lilting northern accent, foreign yet familiar, embodying that sublime sense of difference and distance that unites us on this small island.

His voice is transmitted toward me and, as I stand in my kitchen in Dublin, he talks of getting warm under a duvet on a frozen boat. He is reading a piece about a famous winter snow of 1947. McMaster talks of his father, who has told him this story about his own father, a postman who carried his bike while delivering post in that snow.

Our parents stories are the backdrop on which we make our own, McMaster reads, clearing all of the air from his place on the waves.

My mother as a young woman, circa 1966 | Photographer unknown

I think more about parents and stories. When my mother died, it took me by surprise that the profound loss of her stories, from back then or anymore, was such an immediate and sharp part of my grief. In the last times I visited her, her mind was reliving her greatest hits. It was like at the Oscars when they pay tribute to an actor lost that year and we sit in thrall and in silence finally attending their best scenes.

My mother would tell me her stories, some true, some imagined, and I would listen with more concentration that I have ever since mustered, trying to find her again, trying to find me, or more honestly to not lose me.

After McMaster, with grief a house guest, I pick up again Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking. I am relieved that this concern for the self appears to be ok; that is, it seems to be typical that, as Didion suggests, when we mourn our losses we also mourn, for better or for worse, ourselves.

I miss my mother but, I also miss me, the me that was alive for as long as she was, the me, that only she knew, the me that now I know, as each day passes, I will never, ever recover.

*****

A Good Drawer Never Rubs Out

Adam (Andrew Scott) | Still from All of Us Strangers, 2023 | Copyright Andrew Haigh

Later in the month I am driving to middle of Ireland at 8am on a Saturday to an exhibition. I listen to Irish actor Andrew Scott on the podcast, This Cultural Life. Scott talks of two mothers; that of Adam, the character he plays in All of Us Strangers, and his own mother Nora, who was an art teacher.

He attributes much of his own success to her setting such clear conditions for his creative direction as a child. Her great thing, he recalls, is that she would say that, a great drawer never rubs out. His mother never wanted him to erase his mistakes, but, in the likely event that he made them, she urged him to fully commit and not to retreat, to embrace imperfection, and to draw another line and then one more, as he says with flair.

Scott talks also about his unnamed mother in All of Us Strangers. In the film, the character of Adam, a writer in his forties, is in some kind of recovery, his grief at the loss of his parents, when a boy of just 12, still profound. He conjurs up their ghosts to visit them at home and tell them about who he really is now and who they feared he was then. It doesn’t take much to go back there, says Adam to his lover Harry in the film, referring to the physical suburban house, but also the very moment when his life became defined as ‘before’ and ‘after’ in the most irreversible way.

Mother (Claire Bell) and Adam (Andrew Scott) | Still from All of Us Strangers, 2023 | Copyright Andrew Haigh

But, it doesn’t take much to go back, because Adam can’t ever leave. In an imagined scene, Adam, as an adult, assures his mother he has turned out ok, he is fine, his being gay is not something she need worry about. And yet, by dying, she remains stuck at the moment where his being gay was all she worried about, a time of AIDS and Thatcher and thugs.

So far out of reach he cannot come out, and for much of the film he’s shown staying in, in a half-finished, bleak London building. It is no wonder that Adam is a writer. It is futile, nothing can come of it, but words are his means to survive and to hope.

I think, again, of Baldwin as I drive through the toll gate – You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can't.

*****

Thirst

I am unusually nervous. In my mind I force a return to the basement of le Bal Blomet in Paris some days before. Bastion Briset had chrome metal heels on his shoes with which he pulsed piano pedals. When he slipped a shoe on each foot and his hand touched metal did he awake and know it was showtime? I zip up the metal trimmed collar on my shirt, the cold, sharp teeth biting my neck, bit by bit. In Paris they close the bar when performers perform. There must be no drinking, no distraction, no movement, no chat. These days in Dublin, there only seems to be thirst.

*****

I Want to Talk to You Without Speaking

Lee (Daniel Craig), Still from Queer, 2024 | Copyright Luca Guadaglino

I go to the Lighthouse cinema to see Queer. William is quite drunk in a bar in Mexico, standing and talking to a still distant, elegantly aloof and attired, Eugene.

I want to talk to you without speaking, William says, sweating in the heat, stumbling, a charming if clumsy tactic of seduction. It is for certain a signpost of desire, already even a declaration of his intention to love, an admission of his inability not to.

The difficulty is to convince someone else he is a part of you, William elaborates later to his friend in reference to Eugene. I swallow my beer in the dark, and for a moment, I am there at their table.

William, that is not the - I begin to say but I stop. His eye catches mine, he looks away and returns, dropping his head to the bottom of the golden-glow glass.

Don’t, don’t, he says, glass against lip, talking without speaking, urging I commit to it too.

Lee (Daniel Craig) and Joe (Jason Schwartzman) at the Bar, Still from Queer, 2024 | Copyright Luca Guadaglino

*****

Don’t Forget to Remember

Abestos at the National Gallery, January 2025 | Photo Emmett Scanlon

On another Sunday in January I am with my friend in the National Gallery to witness artist Asbestos perform his work Don’t Forget to Remember.

An evolution of the documentary of the same name, crowds are gathering to watch. We arrive shortly before he carefully wipes away another chalk drawing, framed and hung on the wall, one of 15 to be so erased over this weekend. The drawings, various portraits of his mother and family, have been shown before and have been out it in the city, in bars or on streets for some time, available in the public realm, altered, tagged, claimed by others, as is the way with much of his work. Now they are gathered together in the gallery, a reunion, with the artist, it seems, about to break up this party for good.

Don’t Forget to Remember is made through film and other forms of art for his mother, her Alzheimer’s, and their shared loss of her fading memory. In the film the artist, the son, admits of his mother that, there are so many conversations that I’d love to have and so many things that I would like to have found out about her.

It seems he too mourns the stories.

Abestos at the National Gallery, January 2025 | Photo Emmett Scanlon

As he performs, I notice how relaxed he seems, how his shoulders are low, his movement easy. He says nothing, offers no invitation, but somehow we as an audience are included, welcome, necessary. This work is so conceptually clear, so beautifully staged, intricate in its detail, and so human in its warmth, I feel unexpectedly and quickly present. I am there and nowhere else and this is a relief.

He takes his time as he works, or rather he works as long as it takes. Someone nearby tells me that earlier today a drawing took far longer to erase. It not only had chalk, but collage and paper too they say. I guess it had flair I reply to their surprise, then wondering was it harder to rub out because Asbestos had made more mistakes.

Once the drawing is erased with water and pad, he repaints the board, readying it for some future use, a conceptual and literal burnished, blank canvass, there on the National Gallery wall.

Shortly, out on the street, when he has unlocked his bike, I hug my friend goodbye, a little longer than usual. I am aware that the memories and stories of the artist still erasing inside, if not literally shared by experience, have now, through his actions, been embodied in me.

Any moment now, those stories will gather with mine, amplifying them, inviting me to confront them to not lose them, and I will want this and not want it, and I hold on to the hug for as long as I can, so to resist any urge to let go.

The jar of things removed | Abestos at the National Gallery, January 2025 | Photo Emmett Scanlon

*****

One Dies Every Minute

Paris, Bellville. La Nuit de la Renovation. Anne Lacaton, dressed in a silver-grey coat stands in the room and says that one building is demolished in Europe each minute. She speaks for nine, my metro ride takes thirteen.

Qu’avons nous perdu? Comment récoupérons-nous?

Nous devrions raconter les histoires perdues!

*****

That They May Not Be Forgotten

Tour Group, Still from A Real Pain, 2024 | Copyright Jesse Eisenberg

The following is a transcript from a scene in the film A Real Pain. American cousins David and Benji have gone to Poland on a tour to engage with their Jewish heritage and to visit the former home of their Grandmother who has recently died. They are on a group tour through Poland with strangers, led by a tour guide named James. A trip to Poland’s oldest ceremony becomes a site for an exasperated Benji to address what he sees are some deficits of the tour and his increasing frustration about how the reality of the holocaust and Jewish heritage is being consumed by him and his cousin.

James – You all right, Benji?

Benji – Hey, look, man, you’re, like, completely knowledgeable about this shit. And it’s fuckin’… It’s… It’s impressive, man. And we all know that now and everything. But, like… Like, these are real people, James, you know? They’re not your little factoids lying under here, okay? They’re not history lessons.

David – Benji, Benji, okay.

Benji – Just… Hey, maybe, like, take a seat. Text your wife. Have a sit for a second. Sorry if I said something to upset you or…

James – No. No, no, no. Look, look.

Benji – You know your shit. Don’t get me wrong. And, Eloge, you, like, totally know your shit, but I think it’s just the constant barrage of stats. It’s making this whole thing feel very cold, you know?

James – Okay. Er…I’m sorry. M-Maybe it’s just my British tone or something. I’m just trying to be honest.

Benji – Okay. If it helps to have feedback, that’s what I’m doing.

James – Okay.

Benji – And I just think a major problem with your tour…

David – Oh, my God.

Benji – If I can just…This is okay? This is a free space?

James – Okay. [exhales]

Benji – I just think we’ve been, like, completely cut off from anything that’s, like, fucking… [grunts] like, real, you know?

James – It’s all real, Benji.

Benji – Is it?

James – I’ve only said real things.

Benji – It’s real? Then how come I haven’t met anyone that’s actually Polish?

James – I’ve only said real things.

Benji – I haven’t had any interaction with somebody who’s, like, from here. You know what I mean?

David – Benji, come on.

Benji – We’ve just been going from one touristy thing to another touristy thing to… [imitates blabbing] you know?

James – Yeah, no, but that sort of is what a tour is, though, isn’t it? Going from one touristy thing to another. That’s kind of what you signed up for, isn’t it?

Benji – Well, Dave signed up for the tour.

James – All right. Yeah, no. I mean, I’m sorry.

Benji – Mm-hmm. Look, man. And you know what? Honestly, it’s like a mostly amazing tour.

James – Mm-hmm.

Benji – I mean it, man. Like, I’m fuckin’… I’m lovin’ it. It’s totally Dave’s speed. But just, like, chill on the facts and figures for just a little bit. I mean, would that be cool?

James – No. Yeah, ‘course. Yeah. Let’s tone it down.

Benji – Great. Cool, that’s all. That’s all I’m asking.

James (Will Sharpe) and Benji (Kieran Culkin) debate the tour while Eloge (Kurt Egyiawan) looks on | Copyright Jesse Eisenberg

James – Erm…Well, what I was gonna suggest was we could put a rock on…[hesitantly] er, Kopelman’s headstone.

Benji – Yeah.

James – Yeah?

Benji – Fuckin’ love that idea. No, I think that’s a good idea. Thanks, man.

James – So can I call them over?

Benji – Do whatever you want, man. It’s your tour, James.

James – Okay, if everybody could just come over here for a moment? Everybody? Marcia? Everyone look for stones. Here we go. Look, here’s one.

Eloge – Yeah. Yeah, no problem.

James – Erm…If I can just very quickly… Yeah. This is the oldest tombstone in all of Poland. Erm, and it belongs to a man called Jacob Kopelman Levi, who was a real human person who lived, er, in the real world. He was Polish. Er, from Poland. And Benji and I were just discussing what might be nice to do, and we thought maybe we could all put a stone on his grave. Erm, various theories about this Jewish tradition. But personally, I like to think it’s just a simple warm gesture to say, er, “You’re not forgotten.”

Benji – That was beautiful, James. Thank you. Okay. Erm, so, let’s do that, shall we? Everyone? Should we try and find some nice stones?

Eloge – Yeah. Yes.

Benji – Yeah, that was great.

Eloge – Good idea.

Benji – Yeah.

Eloge – I’ll go look for a stone.

Jesse Eisenberg, Still from A Real Pain, 2024 | Copyright Jesse Eisenberg